Annelotte janse delves into the influences of the kkk on the german neo-nazi manfred roeder and its effects on the german society

Annelotte Janse

Annelotte Janse is a PhD-Candidate in Security History at Utrecht University. Her research focuses on right-wing extremist violence and terrorism in the post-war Western world.

Threat perceptions at an international white supremacist congress, September 1976

While an international community of scholars and politicians thought Nazism to be either defeated or confined to national borders, American Klansmen David Duke and James K. Warner organised the first ‘World Nationalist Congress’ in Duke’s homebase of Metairie, Louisiana, between 8 and 11 September 1976.

One of the participants was Manfred Roeder (1929-2014), a German neo-Nazi. He had planned a five-week journey across the United States to attend the congress and forge ties with overseas comrades. Then still unknown beyond West Germany, Roeder would go down in history as the leader of the Deutsche Aktionsgruppen (DA, German Action Groups), a right-wing terrorist group responsible for the first post-war racially-motivated terrorist attacks in West Germany.

The men and women whom Roeder met at this international suit-and-tie assembly of right-wing extremists, decisively shaped and sharpened his perceptions of threat and, ultimately, his understanding of security. Revisiting the World Nationalist Congress helps foreground the importance of security thinking in brokering transnational extreme-right connections, and charting its lasting, unsettling consequences.

A two-tiered American threat perception

Brimming with virulent racism and antisemitism, Duke and Warner touted the World Congress as ‘historic’ and a monumental stride for ‘the White Race (…) in our fight to save Western Civilisation.’ Right-wing extremists all over the world had eagerly awaited the international gathering and more than 300 neo-Nazis, white supremacists, and segregationists from the American continents and Europe flocked to Metairie as invitees. Upon arriving, Roeder engaged with many American extremists and segregationists who perceived the Civil Rights Movement, devoted to ending American racial segregationist policies, as a grave threat to the white race.

In the antisemitic mindset of these segregationists, the threat of ‘racial mixing’ was in fact dual-layered: Black people had become a proxy of the alleged international Jewish conspiracy intent on dominating the world. This conspiratorial view thus implicated Jewish people in ‘racial chaos’. Roeder joined the racist, antisemitic chorus, applauding the refreshing ‘clarity’ with which the ‘race and jewish problem’ was discussed.

The Congress report trumpeted that all Congress attendees had ‘unanimously’ declared the Jewish people as ‘the source’ of global problems. ‘The time had arrived,’ the report continued, ‘to declare open war against’ them. The conference thereby further entrenched the perception of a Jewish global conspiracy into right-wing extremist imaginations of white imperilment.

A ‘Copernican turning point’

Roeder called the Congress ‘a Copernican turning point’. Through his encounters, he absorbed the American two-tiered threat perception and began adopting racist, anti-Black rhetoric alongside his pre-existing antisemitic views. Conspicuously absent from Roeder’s writings predating September 1976, skin colour now emerged as a new mechanism of exclusion.

In his 40th newsletter, for example, Roeder shared details of American cities he visited during his roundtrip. He bemoaned the arrival of ‘coloured people’ (‘der Farbige’) into cities now ‘teeming with the most confused mixture of peoples’ and attributed the ‘unimaginable (…) racial chaos’ to desegregationist policies. Roeder also merged the American two-tiered threat perception with his own when he warned that ‘One must know that behind the black-white racial problem, too, there are only Jewish masterminds’, identifying the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) as a purportedly Jewish front.

The German ‘asylum question’

The physical, real-world effects of Roeder’s adoption of the American threat perception became painfully clear in 1979-1980. Having spent two years in self-proclaimed ‘exile’ after fleeing West Germany to escape a prison sentence in January 1978, Roeder returned in December 1979. He soon noted that one political question in particular dominated public and political debate: the ‘asylum question’.

Between 1979 and 1981, a ‘sudden spike’ of asylum seekers entered West Germany. Whereas between 1953 and 1978 an average of 7,100 people sought political refuge in West Germany annually, 108,000 people applied for asylum in 1980. As migration historian Rita Chin noted, Turkey’s military coup in 1980, the introduction of martial law in Poland in 1980-1, and the arrival of Vietnamese refugees in West Germany explained the rising number.

With the asylum seekers’ arrival, German citizens began to send hundreds of abusive and threatening letters to regional and federal interior ministers, urging them to halt ‘the destruction of the German race’. As a consequence, the ‘asylum question’ rapidly politicised and sparked outrage. In several articles in Der Spiegel, journalists keenly quoted the letters’ most vitriolic parts, adding to the sense of alarm. A ‘moderate form’ of xenophobia, other journalists noted, prevailed among more than half of the Germans.

Recontextualising American security imaginaries to German Society

As Roeder coupled the Germany ‘asylum question’ to his impressions of the American ‘multi-racial’ society, it became the prism through which he viewed the world. He predicted that integration would fail and, falling back on his experiences of America as ‘prime example’ of a ‘multi-racial’ society, underscored his dystopian view of Germany’s future:

I have been to America, to South America and often to South Africa. I can compare. I have seen the racial problems, the outbreaks of violence that must take place in any multiracial society. (…) And that will happen on a much bloodier scale here in Europe too, because we are smaller and more uptight everywhere.

Roeder’s prediction, in turn, transformed into the driver and justification of the terrorist violence that he subsequently sanctioned.

The Deutsche Aktionsgruppen and racially motivated terrorism

Between late 1979 and September 1, 1980, Roeder and three others formed the Deutsche Aktionsgruppen (DA). Its main goals included among others ‘scaring foreigners’ and deporting them from the country, to thereby liberate the German people from ‘foreign influences’.

As one member attested in court later, ‘the asylum seeker problem was actually always on the agenda’ in conversations with Roeder. Nudging them towards violence, Roeder constantly repeated to DA-members that ‘something could be done about it.’

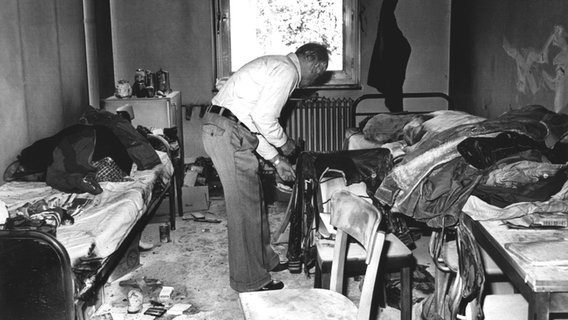

In July and August 1980, the DA committed four attacks on asylum seekers’ homes and refugee shelters. The perpetrators selected their victims based on their non-white skin colour. For example, two DA-members scouted an asylum seekers’ home and check for, as the judge recorded in the verdict, ‘dark-skinned people’, before deciding to attack. On August 22, 1980, the final bomb attack against a temporary asylum seekers’ centre in Hamburg killed two Vietnamese. It was the first racially motivated terrorist attack in post-war Germany. Celebrating the attack, Roeder marked the day with the phrase ‘liberation starts’ in his diary.

In 1982, Roeder was sentenced to thirteen years imprisonment for being a ringleader of a terrorist organisation and attempted incitement to murder.

The violence executed by Roeder’s DA pointed to the successful recontextualization and transmission of Roeder’s Americanised security thinking as it coalesced with changing circumstances in West German society. By instigating the DA-members to use violence against people of colour, Roeder set a new standard and singled out a new victim for other right-wing extremists to emulate up until the present.

While this transfer of security thinking shows the flexibility and adaptability of right-wing extreme perceptions of threat and enemy in the past, it also reminds us that extreme right-wing development and dynamics, whether present or past, rarely occur in an exclusively domestic vacuum.

COVER IMAGE: The room of the two Vietnamese victims, Đỗ Anh Lân and Nguyễn Ngọc Châu, in the asylum seekers centre in the Halskestrasse, Hamburg, NDR.de

Opinion pieces have been published by the Security History Network for the purpose of encouraging informed discussions and debates on topics surrounding security history. The views expressed by authors do not necessarily represent the views of the SHN, its partners, convenors or members.

One thought on “Manfred Roeder at the Klan’s ‘World National Congress’ and racial terrorism against ‘foreigners’”

Comments are closed.