Dr. Enno Maessen

Enno Maessen is an Assistant Professor of History at Utrecht University. His research focus is on urban history, modern Turkey and the Eastern Mediterranean, social movements and the politics of representation in the second half of the twentieth century.

‘It was with no pain at all that I left the useless desert for the riotous wonder of Istanbul. My colleagues were scattered around the dreary apartment blocks of Pera, but I had no intention of following their lead. Within a few days I had found a delightful villa in Beylerbey[i], on the Asiatic shore of the Bosphorus, a place of such loveliness that I agreed without demur to pay an exorbitant rent. It was next door to the landing-stage, and for three years I was to commute daily between Asia and Europe by ferryboat, through the everchanging pattern of gulls and shearwaters, mists, currents and eddies. The old Turkey hands, of course, were aghast. But it is a good working rule, wherever you are, to ignore the old hands; their mentalities grow inward like toenails. I had no cause to regret the choice of my remote Asian hide-out.’

This is how a former Istanbul station chief of the MI6 narrates his time along the Bosporus in the early years of the Cold War. While on mission, he had recognized and appreciated the beauty of Istanbul’s unique location on two continents, its landmasses divided by a sea strait: the Bosporus. Here, I will discuss a number of examples of how the Bosporus featured as a geopolitical and cultural axis during the long twentieth century, converging towards the Cold War.

Pomp and Power

Since centuries, the Bosporus had been a strategic axis connecting the Black Sea with the Marmara Sea. It had historically been a critical artery for commerce, cultural transference and warfare. In Byzantine times it was revered for its beauties and feared for its dangerous currents. Fleets would have to gather at both ends, anticipating suitable weather conditions, which made them vulnerable for pirates and enemies. Sultan Mehmed II, a year prior to conquering the Byzantine capital in 1453, had a fortress called Rumeli Hisarı built on the European side of the Bosporus to cut off the city from support from the Black Sea. He followed in his grandfather’s footsteps who had already built a similar fortress, Anadolu Hisarı, on the Anatolian side.

Particularly during the nineteenth century, the Bosporus became increasingly important in the representation of power. Shore houses, the summer residences of foreign legations and the Ottoman dynasties, rose in number and size. Around the same time the centre of Constantinople’s foreign presence, Pera, became the site for increasingly pompous embassy buildings with pristine views of the Bosporus, Golden Horn and Marmara Sea. More importantly, these buildings’ façades were very visible for those arriving to Constantinople by boat, as an architectural reflection of the changing balance of powers in the Eastern Mediterranean. Some travellers apparently even mistook the majestic Russian embassy for the dynastic residence of the Sultan. The situation was probably to the dismay of the Ottoman court, who ordered the construction of a new grand palace at the shores of the Bosporus, known as Dolmabahçe Palace.

Controlling the Straits

Control over the Bosporus became one of the incentives for the Russian Empire to start the Russo-Turkish war between 1877-78 and for Allied forces to start the Gallipoli campaign in 1915 during World War I. After World War I the sea strait was briefly international territory, stipulated by the Treaty of Sèvres in 1920, until its status was renegotiated in the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923. As the Ottoman Empire was dissolved, the newly founded Republic of Turkey gained sovereignty over the Bosporus and Dardanelles straits, although it was obliged to let all commercial and military maritime traffic pass through and demilitarize the straits’ shores.

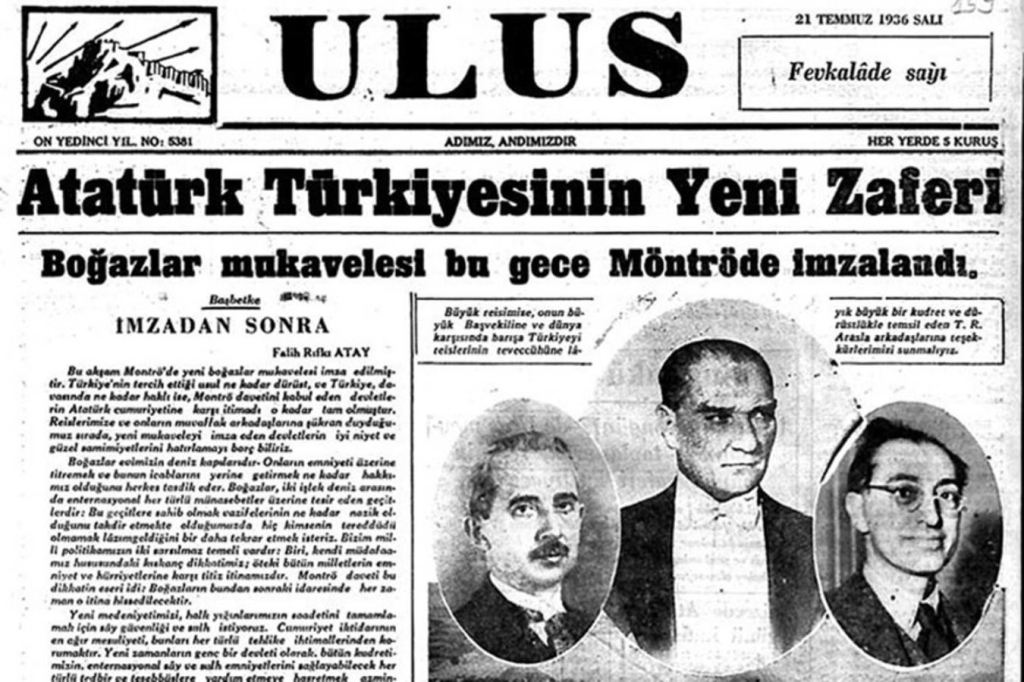

In an atmosphere of rising geopolitical tension, Turkey had clandestinely refortified the Dardanelles and Bosporus straits by the early 1930s, but also made efforts to renegotiate the status of the straits by the mid-1930s. Turkey feared regional remilitarization in the region and the limited protection offered to its territory in the event of a foreign act of aggression. The 1936 Treaty of Montreux therefore regulated the traffic on the Bosporus, granting free passage to commercial vessels in peacetime, but imposed restrictions on the passage of warships during wartime.

Turkey managed to sustain a complex or ‘active neutrality’ in World War II until February 1945 when it finally joined the Allied camp. Tension ensued over the straits, however, when Turkey rejected Soviet claims for the passage of their warships and the erection of naval bases. These claims further escalated after World War II, as the naval presence of the USSR in the Black Sea increased. This prompted Turkey to ask the United States for support and set in motion Turkey’s stronger alignment with the American sphere of influence. This eventually culminated in the Truman doctrine and, in 1952, Turkey’s accession to NATO.

From Fact to Fiction

During the Cold War the Bosporus would retain its geopolitical significance as it became the scene of extensive monitoring facilities of intelligence agencies, who tracked Soviet naval activity in the Turkish straits. American, British and French attaches and spies were not the only ones to monitor Cold War Bosporus traffic. It was a popular pastime. Nobel laureate and acclaimed writer Orhan Pamuk narrates how, as a young boy in the early 1960s, he would count Soviet warships. Istanbul’s status as one of the World War II and Cold War spy capital had major effects on the city’s representation in literature. During the Cold War it quickly became a preferred setting for all kinds of espionage thrillers and movies, from Ian Fleming’s 007 stories to the oeuvre of former MI6 officer David Cornwell (pen name John le Carré).

Sometimes, reality and fiction merged in Istanbul. The anonymous station chief at the beginning of this blog, presents us with precisely such a story. He was not just an anonymous career spy, but none other than Kim Philby: one of the most legendary double agents in Cold War history. He coordinated the recruitment of potential agents in Southeastern Europe for MI6 between 1946 and 1949, but had been a double agent for the KGB since the 1930s. Among the colleagues that Philby exposed was Cornwell/John le Carré, who dramatized Philby’s story in one of his key works Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy. Philby rented a shore house villa or yalı in Beylerbeyi from the writer Münevver Ayaşlı. Allegedly, he would jump straight from his bedroom into the Bosporus for a morning swim.

Soft Power through Hospitality

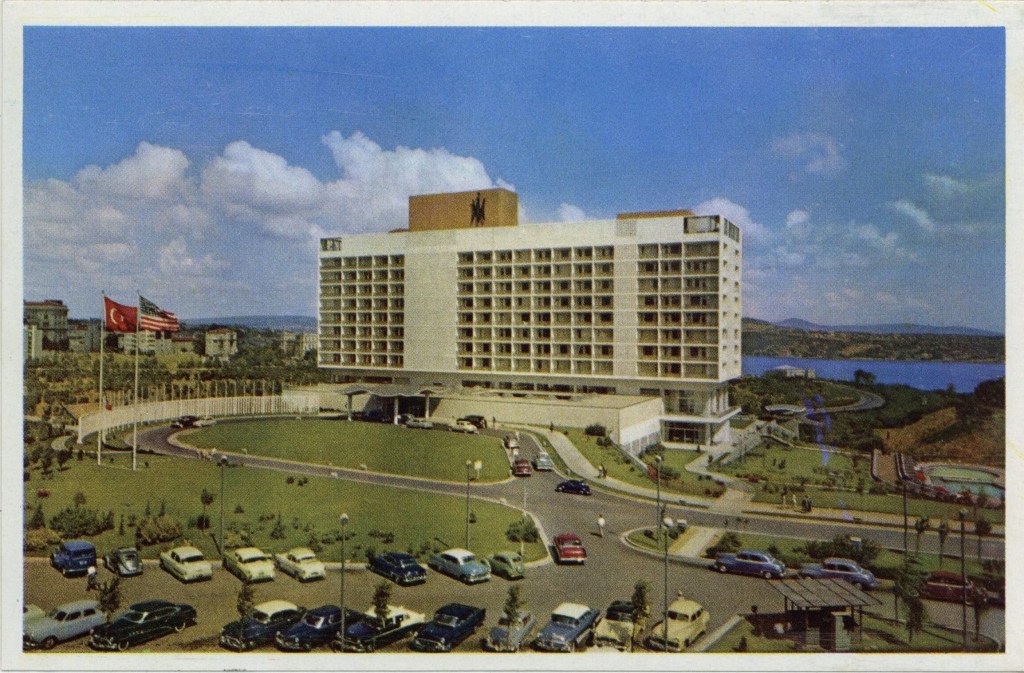

During the 1950s, the Bosporus also became the sight of another form of Cold War politics. Similar to the ways in which foreign powers had established their visual presence with palatial embassy buildings facing the Bosporus, a major US corporation now established an enormous modernist hotel, towering over the hills along the Bosporus. The Hilton Hotel was presented as a landmark of US-Turkish cooperation and a very visible example of US soft power, similar to Hilton hotels in Cairo and Athens established around the same years. Conrad Hilton himself explained the hotel’s rationale: ‘We mean these hotels too as a challenge (…) to the way of life preached by the Communist world’. The hotel thus intended to signify Turkey’s Cold War marriage with ‘westernization’ and capitalism – a white colossus in the Internationalist style for everyone passing through the Bosporus to see.

Seeking Refuge in Istanbul

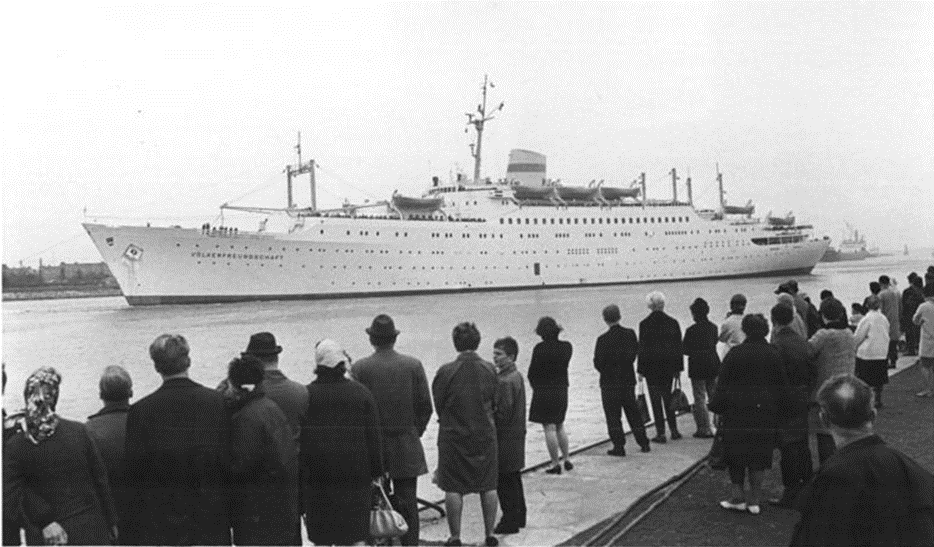

During the 1960s and 1970s the Bosporus witnessed the perilous stories of those who tried to slip through the Iron Curtain. The GDR cruise ship Völkerfreundschaft would regularly pass through the Bosporus for cruises along Varna, Yalta and Sochi. Whenever the ship would pass through the Turkish strait passengers would try to jump off and take their chance to reach the shore. Eventually, this prompted the GDR authorities to post men with bats along the rails and install screens to prevent these dramatic disembarkings. Regardless, a German pastor and resident of Istanbul, would prepare rowing boats whenever news reached him that the Völkerfreundschaft would pass through the Bosporus, in order to rescue potential refugees.

Yet Istanbul housed other refugees too. A prominent escapee who could be found in the city was the American writer and civil rights activist James Baldwin, who stayed for extensive periods during the 1960s. He too found a mansion along the Bosphorus, once owned by diplomat and scholar Ahmed Vefik Paşa, right next to the fortress Mehmet II had built in 1452. Escaping another kind of repression – the civil rights struggle, racism and homophobia – Baldwin managed to take distance from the day-to-day pressures of living in the United States. Like Pamuk and other Istanbulites, he also watched ships passing through, although he remarked mostly the US ones: ‘The American power follows one everywhere’.

The Bosporus’ surroundings have quite dramatically changed since the height of the Cold War, in sync with Istanbul’s rapid urbanization. It is now crossed by three suspense bridges, a submerged rail tunnel and road tunnel. The strait’s geopolitical significance, however, remains at an all-time high, in the midst of new wars and alliances around the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea (e.g. wars in Syria, Ukraine, Palestine, the renewed significance of NATO and Turkey’s ties with Russia, Israel and Hamas).

COVER IMAGE: View of the Bosporus from the Rumeli Hisarı. Salt Research, Nazif Topçuoğlu (1999).

Opinion pieces have been published by the Security History Network for the purpose of encouraging informed discussions and debates on topics surrounding security history. The views expressed by authors do not necessarily represent the views of the SHN, its partners, convenors or members.