Benjamin Duerr

Benjamin Duerr is a political scientist, legal scholar and writer. He specializes in international relations, multilateral organizations and the international rule of law.

Is arms control a luxury that states can only afford in times of peace? As the threat of war returns to Europe and states strengthen their military capabilities in the face of a possible Russian aggression, an old fear re-emerges: the concern that international law could curtail a country’s military strength and jeopardise its security.

In recent weeks, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Finland have announced their intention to withdraw from the treaty that bans anti-personnel landmines, also known as the Ottawa Convention. The governments state that their militaries need the ‘flexibility and freedom of choice to potentially use new weapons systems’. The treaty, they imply, only hinders such flexibility. In March, Lithuania also withdrew from the convention that prohibits the use of cluster munition, citing the need to maintain ‘a full spectrum of defensive tools, including cluster munitions, to ensure national security’. These developments are seen as an increasing erosion and decline of the arms control and disarmament regimes.

Balancing national secrutiy in common interests

Since the early modern arms control and disarmament efforts, the fear that international treaties could jeopardise a country’s security has often weakened or prevented agreements. Already in 1139, a prohibition of the crossbow by Pope Innocent II failed as the weapon was seen as necessary and too effective to be set aside. At the core of such negotiations is the balance between the security interests of states on the one hand, and the common interest of limiting warfare on the other hand.

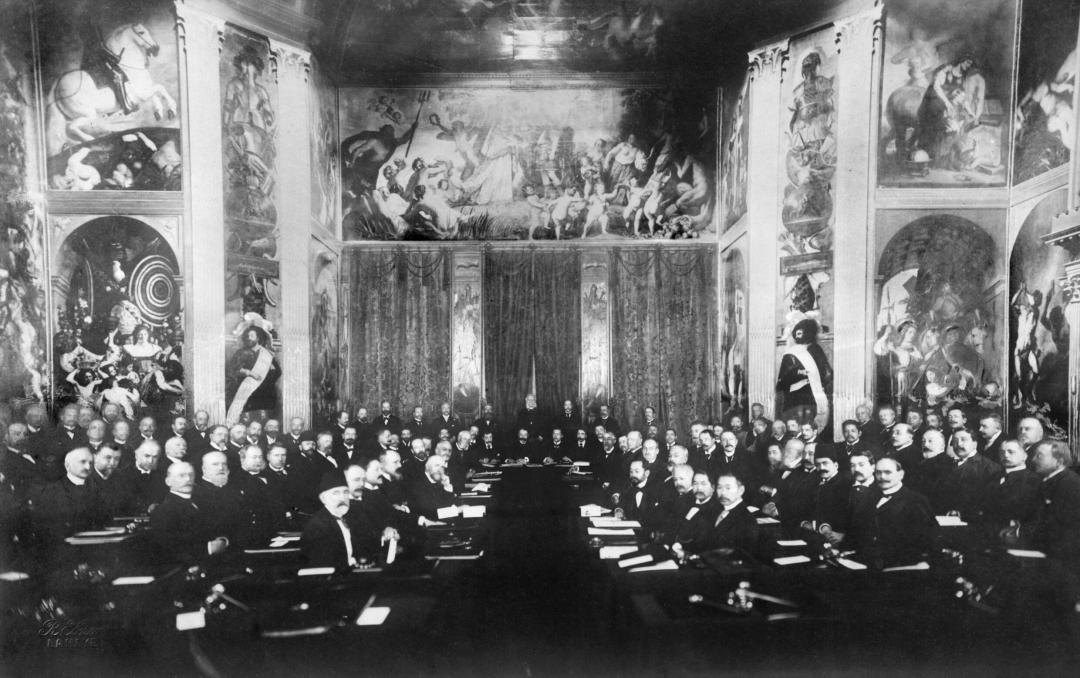

The Hague Conferences of 1899 and 1907, often regarded as the beginning of modern arms control among European states, are a historic case in point. Initiated by the Russian government and hosted by the Netherlands, the conferences were convened to establish, among others, limits on the rising armaments at the end of the nineteenth century. With more than 20 participating states in 1899 and more than 40 in 1907, they became major international events and marked a crucial moment in the history of international law.

Dum-dum bullets and chemical weapons

One of the proposals discussed in The Hague in 1899 was the prohibition of the use of expanding bullets, so-called dum-dum bullets, as they were causing particular pain when they entered the body. The British delegate, General Sir John Ardagh, explained, however, that these bullets remained necessary in colonial wars as opponents would not be complying with a prohibition. A prohibition, therefore, would put the own forces in a disadvantaged position. ‘[B]efore anyone has time to explain to him that he is flagrantly violating the decisions of the Hague Conference, he cuts off your head’, Ardagh told the delegates. A legal prohibition, he implied, would jeopardise British security interests and, therefore, he reasoned that ‘projectiles of sufficient efficacy against savage populations’ remained necessary.

The proposal to prohibit the use of asphyxiating and deleterious gases triggered similar discussions in The Hague. Even though the industrial production of chemical substances was in its infancy at that time and chemical weapons had not been used yet, the threat of chemical warfare loomed on the horizon.

The American delegate, Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan, was particularly outspoken against a prohibition. He argued that the United States, as an ascending global power, might be compelled to wage war in the future. ‘[I]t is therefore a question of not depriving oneself, by means of resolutions hastily reached, of means which later on might be usefully employed’, the minutes of the conference quote him as saying. Mahan’s intervention expressed a fear shared by several military delegates that the proposed agreements and treaties could limit their countries’ defence capabilities now or in the future.

‘Not sacrificing the security of our country’

In the years after 1899, international tensions and armaments increased further. When a second Hague Conference was prepared, scheduled to take place in 1907, the German Empire was opposed to even put arms control or disarmament on the agenda. The government in Berlin argued that the international legal system would first need to be developed further. At this stage, arms control was impossible for various practical reasons, such as the lack of verification mechanisms. Germany even went so far to claim that discussions on arms control at The Hague could threaten international peace as the diverging positions of states on this issue could trigger new conflicts.

Behind the German opposition to discussions on arms control at the Hague Conference, however, was the fear that an agreement would jeopardise German armament plans and its security. Germany feared rising tensions and, in particular, British armaments. In 1899, emperor Wilhelm II had already declared in a memo that ‘in practice, I will […] only rely on god and my sharp sword.’

German chancellor Bernhard von Bülow, too, distrusted any agreement and the ‘empty phrases of quixotic dreamers.’ ‘Of course, I never thought about sacrificing the security of our country for the hypocritical assurances by our enemies,’ he wrote in his memoires about the 1907 Hague Conference.

Arms control results at the Hague Conferences

Both Hague Conferences failed to reach an agreement on disarmament, but achieved results on arms control on several issues. A majority of countries agreed in 1899 to a prohibition on asphyxiating and deleterious gases, dum-dum bullets, and – for a period of five years – the launch of projectiles and explosives from balloons. In 1907, submarine contact mines were banned. The success of the negotiations were to a large extent the result of public pressure.

The majority of countries at the Hague Conferences believed that certain weapons were inhumane or that they would benefit more from an international agreement banning those weapons than from the military advantage they would get by using them.

More than 125 years after the first arms control attempts, those tensions have not been fully resolved. Transparency through international organisations and mechanisms for accountability in cases of violations have reduced fears. However, security and compliance with international law are still often seen as a (false) dichotomy.

COVER IMAGE: The First Hague Conference in 1899: A meeting in the Orange Hall of Huis ten Bosch Palace. Wikimedia Commons.

Opinion pieces have been published by the Security History Network for the purpose of encouraging informed discussions and debates on topics surrounding security history. The views expressed by authors do not necessarily represent the views of the SHN, its partners, convenors or members.