Magnus Gislason

Magnus Fage Gislason is a bachelor’s student of Philosophy, Politics, Economics and History (PPE) at Utrecht University. He wrote this piece as part of the course Historicizing Security – in Europe and beyond.

The Paris Commune of 1871, proclaimed on 28 March, was a security issue of the first order. France had been invaded by the Prussians, the emperor had been captured at the battle of Sedan, and a siege of Paris had turned into a revolutionary uprising inside Paris.

From the perspective of the French state, the situation was catastrophic. The Paris Commune established itself as a polity, challenging the power and legitimacy of the French state. This strained situation, however, also makes it possible to view the events as a security issue from the perspective of the communards. This shift in perspective is supported by tracing the emergence of a communard ‘security culture’, defined as: a shared understanding of what should be protected, what this needs protection from and institutions or practices developed to enforce this protection.

I argue that, while no coherent institutionalized security culture crystallized during the short life of the Commune, the dominant security culture was indeed challenged as latent, revolutionary ideological currents gained prominence and coalesced in a chaotic process of securitization from below.

‘We must rally as quickly as possible the scattered elements of our heroic army. It has been defeated and disbanded through the treachery of its leaders, and has proved incapable of defending the country since it was organized for repression.’

Public proclamation by the Central Committee of the Twenty Arrondissements, a body formed during the siege of Paris, prefiguring the Paris Commune. 15th of September 1870.

A security culture vacuum

[W]hen a shameful and hideous peace settlement was rushed through […]; when all the government posts were taken over by men known for their hostility to the Republic; finally, when Paris had to suffer the ultimate humiliation of foreign occupation, then at last it dawned on the innocently trusting people that they could count on no one but themselves to defend their honour and freedom.

This quote stems from a speech given by the secretary of the National Guard of Paris in March 1871. It captures the unique confluence of factors that made it possible to challenge the ideas of the dominant security culture of France. The isolation of Paris caused by the siege is not enough to explain the uprising, since the Parisians, conceived of as co-constituting the existing social and political order, were themselves a securitized subject of the French state. Additionally, three groups of factors converged to create a fracture in the security regime of the French state, which made it possible for political actors within the Commune to contest it.

First and foremost, the most important institution of the French state for ensuring its own security (the military) was in crisis due to the Prussian invasion. This caused the French state to lose control over Paris.

Secondly, socio-economic changes in the city, and in the National Guard of Paris specifically, enabled the rise of a new state-like entity, with capacity to challenge the existing security culture. Thousands of affluent citizens had fled Paris in anticipation of Prussian advances. In the economic standstill that followed, partly motivated by the prospect of allowances for them and their families, the socio-economic composition of the National Guard shifted towards the working class. This was significant because the National Guard historically had been made up of the middle classes. Unlike conventional armies, it had internal democratic structures that enabled it to become a political body with military power.

Lastly, tensions in the prevailing security culture corroded its legitimacy within Paris. The French establishment was faced with a dilemma between protecting the territorial sovereignty of the French state and the bourgeois social order. This tension came to the fore with the signing of a peace treaty with the Prussians in February 1871. The unpopularity of this agreement further deepened Parisians’ sense of isolation from the French government, which had also relocated from the capital to Versailles.

The institutional base to enforce the social order of the French state was undermined. Parisians’ ideas about the kind of social order that should be protected, and against what, were then disconnected from any institutions for their enforcement. A vacuum had emerged within Paris in which it was possible for political actors to redefine what should be protected, and from what, by the restructured National Guard. A battle of discursive securitization within the city walls of Paris began.

Paris torn between fear and revolutionary fervour

The Paris Commune emerged in a city defending itself against a Prussian siege but soon transformed into a rebellion against its own government in Versailles. The idea of the Commune, as a new social order to be protected, therefore emerged in a context already ripe with threat perceptions and security measures. This led to the paradoxical situation that the Commune, as a political community to be protected, came into existence, complete with security measures and corresponding threat perceptions, before a clear, shared understanding of what constituted the new social order had formed.

This simultaneous process of securing and defining the Commune took place amidst both emotional and ideological tensions. The prolonged siege, military defeat to the Prussians, and collapse of the former state steeped Parisians in feelings of insecurity. At the same time, the city was characterized by emotions of revolutionary fervour – a willingness to sacrifice safety and security for the sake of other values, as expressed in this letter from a young Parisian man to his family in March 1871:

Tell the country people that we do not want civil war, but if those bandits try to remove us we will burn Paris down rather than let them defeat us […] Let those who declared war pay the costs, along with the dirty capitulators who signed the so-called peace.

In this emotional context, Communards sought legitimacy of their political ideals by appealing to security. Some went beyond defining what should be protected, and from what, and politicized the causes behind contemporary security threats, as in this statement made by the First International in support of the Commune:

The principle of authority has proved incapable of bringing back order to the streets and restoring production in the workshops; by its impotence it has negated itself. The lack of solidarity of interests has led to general ruin and social strife. Liberty, equality and solidarity must be the new foundations on which we will restore order and reorganize labour, the essential condition of order.

By linking security with certain principles of social organisation, “Authority” against “Liberty, equality and solidarity”, the statement radically calls into question the nature of (in)security.

The Defeat of the Commune

Before the disparate threads of an emerging communard security culture could stabilize, the French State regained control of Paris and defeated what it saw as a threat to official social, political and economic order. Troops entered Paris on 21 May 1871. A week later the army proclaimed:

FRENCH REPUBLIC

INHABITANTS OF PARIS

The French Army has come to your rescue.

Paris has been delivered.

At four o’clock our soldiers took the last rebel positions.

At last the fighting is over; order, work and security will reign once more.

The Paris Commune had been defeated, and it is left to imagination whether a Communard security culture ever would have crystallized. Resistance to a centralized and oppressive state was one of the only commonalities across the eclectic uprising. In a struggle for self-management, and against centralized authority, it was exactly the ability to define what should be protected, and from what, that needed protection.

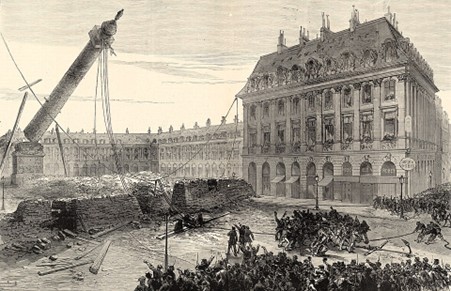

COVER IMAGE: Barricade of a Parisian Street, March 1871. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Opinion pieces have been published by the Security History Network for the purpose of encouraging informed discussions and debates on topics surrounding security history. The views expressed by authors do not necessarily represent the views of the SHN, its partners, convenors or members.