Jossie van Til-Duijsters

Jossie van Til-Duijsters is a PhD-Candidate in Security History at Utrecht University. The title of her PhD project is “The generation of 1813, the new monarchy and her role in the European security culture”

Hopes for the future were high in the newly formed Dutch monarchy in 1814. As Gijsbert Karel van Hogendorp declared in his famous pamphlet of November 1813, the old glorious times would return after the havoc of the Napoleonic Wars. These hopes also related to colonial riches. The Dutch government had reached an agreement with the British about the restitution of the biggest part of the former Dutch colonies, which British troops had occupied following France’s annexation of the Netherlands in 1810. Dutch elites expected that colonial trade would soon be very profitable for the motherland again. But was it that simple to restore the old imperial glory of the seventeenth century, of the so-called ‘Golden Age’?

Nevertheless, the Dutch monarchy was an important imperial power again in 1814. Its first task was to set up a new government in those colonies. In this blog, I will look at the early days of the new, post-1814 Dutch administration on Java and parts of the Indonesian archipelago. Through the private letters that governor G.A.G.Ph. van der Capellen wrote to Minister of State A.R. Falck, we will gain insight into the challenges that came with this restoration of imperial power. These key players had met during their stay at the University of Göttingen in 1800 and both worked in government positions until 1810. As soon as the French left the Netherlands, they again took up their work in government, Falck became the right hand of King William I, while Van der Capellen represented the Dutch government in the Southern Netherlands in 1814-1815.

Colonial ignorance and liberal imperialism

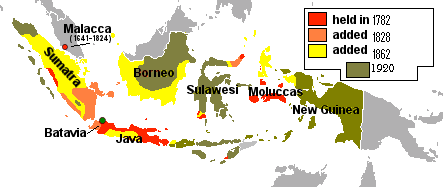

The Dutch constitution of 1814 stated that the supreme government of the colonies was solely in the hands of King William I. The king and most of his secretaries of state had hardly any experience in colonial government. Yet they all favoured a more liberal approach towards imperial rule, based on a general idea of free labour and tax payment, related to the value and size of the land that one owned or leased. Their aim was to improve the prosperity of the local people, mainly to ensure that there would be enough profits for the motherland. With this idea in mind, the three commissioners general, including Van der Capellen, the intended governor, C.T. Elout and rear admiral A.A. Buyskens, set sail to the Indonesian archipelago in 1816.

Van der Capellen encountered his first difficulties on the outward journey to Batavia. It turned out that one ship, the “Braband”, was in a very bad state and had to be replaced in Portsmouth. His chief of staff H.M. de Kock and 750 soldiers were on board, meaning that there was an immediate shortage of troops. De Kock and his men only arrived after a delay of over a year, in May 1817, being just in time to suppress a violent rebellion on the Molucca Islands.

In his letters, Van der Capellen complained that he lacked two important things: funds and knowledge of the archipelago. The scientist Casper Reinwardt had travelled with him to Java and was put in charge of exploring the island. He had to answer various questions about the agricultural possibilities of the island. Yet Van der Capellen also needed to get acquainted with Java himself. He considered knowledge of its landscapes, inhabitants and culture as crucial to the restoration of the colonial government.

Free of forced labour

One particularly important question was whether the authorities should continue the recently introduced system of land rates based on free labour and tax payments, or switch back to the old system of forced labour? The senior civil servant H.W. Muntinghe (1773-1827) explained the difference between these two systems in 1817. Forced labour meant that the Indonesian people had to be subservient to the interests of trade and could not take part in government. The system of tax payments was the opposite, as the Indonesian people would be free to choose their agricultural produce, were taxed in accordance with their income and wealth and should be consulted about matters of taxation. In nearly all his letters, Van der Capellen evaluated the system of land rates as the best possible solution. He considered the associated lack of revenues a temporary malaise, caused by unfamiliarly of the administrators with the new system. He also believed the Javanese people had grown accustomed to more freedom and less repression. Hence it would be a bad idea to revert back to forced labour. Van der Capellen did not doubt that the land rates system needed adjustments to become more profitable, but due to the very poor British accounting there was hardly any in-dept insight of possible revenues to be had.

The British reforms had also remained incomplete. Van der Capellen was very surprised to learn that around Semarang and Preanger the old system of forced labour still existed. There, the Javanese people were forced to supply coffee to the government at a very low price. He found the surprise unpleasant. In his opinion, the administration of a colony could not be so incoherent that different systems of government simultaneously existed within the same territory.

During the closing months of 1817, when he was on his first tour across Java, the governor could actually see now how the land rates system worked. Van der Capellen reached two conclusions. First, he noted how the land rates system was based on the right economic principles of free labour and tax payments. Secondly, he felt that their implementation fell short in nearly all residencies because the British had not consistently applied it. Van der Capellen immediately realised what a huge task it would be to solve this confused situation. He wrote to Falck that it resembled, in a way, the ongoing process of unification in the Netherlands. He was aware of the opposition of the residents (the highest administrators in a district), because they could no longer use their power for their own profit. Yet he saw reform as the only way forward, being convinced that when this system was implemented in a unified way everyone would see the benefits of it and decided to improve the colonial administration to acquire more insight into the possibilities of the land rate system.

Conclusion

The administrative concerns of Van der Capellen indicate that the European revolutions and Napoleonic Wars left their traces in the colonies. It took time, people and money to restore imperial peace and order, which was further complicated by post-war scarcity. On a more intellectual level, the newly appointed governors also faced the challenge of how to introduce new ideas from the revolutionary period, such as liberal policies of free labour, taxation and centralisation. Van der Capellen’s letters show us what difficulties he met in this transitional phase of imperial restoration. Although he certainly supported plans to improve the prosperity of the local people, there is no indication in his letters that the inhabitants, or even the Javanese elite, were consulted on governmental decisions concerning their future.

Van der Capellen also struggled significantly with another contemporary belief: the conviction that the colonies purely had to serve the metropole and generate as much profit as possible. As I have written elsewhere, this call for profit would only increase, much to the detriment of colonial subjects and the stability of Van der Capellen’s governorship.

COVER IMAGE: Portrait of governor G.A.G.Ph. van der Capellen, painted by Cornelis Kruseman, Wikimedia Commons.

Opinion pieces have been published by the Security History Network for the purpose of encouraging informed discussions and debates on topics surrounding security history. The views expressed by authors do not necessarily represent the views of the SHN, its partners, convenors or members.